For a long time, I have been wondering about this strange couple formed by the composer and his performer. This relationship of co-dependence is quite unique, and it takes an even stranger turn when current technological means allow today’s composers to write without necessarily being instrumentalists themselves.

While not strictly speaking a creator, the performer is not just a tool either. When I try to explain this to novices, I have come to use this metaphor:

Let’s imagine that the composer is a fashion designer. He builds his own universe, he designs dresses.

I am his seamstress.

Starting with a drawing of the dress, I will create a pattern, cut the fabrics, make a basting… In short, I will sew the dress.

But I’m also the top model: I’m the one who will wear the dress!

In the end, when we think about it, it is the same thing with the “classic” repertoire, except that in this case it is the shaping of a period costume and many tailors have made this model before us. We have seen others wearing it — with more or less success — you can download the patterns, and there are tutorials on YouTube on how to do it step by step… It doesn’t make it easier — it’s a huge job — but let’s just say the way is paved.

I love being the first to assemble a design. I like to imagine how I’m going to make the pattern, choose the fabrics, try things on, consider all the possibilities, take my time to make the basting… That’s usually when I first share “my” dress with its author — it’s not completely finished but you can see what it will look like — to have his approval that the result is similar to what he had in mind when he designed “his” dress. Sometimes it is, sometimes not. Sometimes it’s not quite what he had imagined but he likes it anyway.

Of course, when I get the sketch, I know pretty quickly if the dress is going to fit me or not. If it hides my imperfections, if it highlights my assets; when this is not the case, you have to accept not looking your best…

It’s hard not to put too much of yourself into this exercise. Of course I want to be beautiful in this dress, but it is not about me… It is necessary to know how to accept to be in the background, to be “in the service” of the dress.

You can make a few alterations, but it’s out of the question to transform overalls into an evening gown just because it makes you feel more seductive!

Sometimes I receive extremely precise designs, drawn on grid paper with each seam over-explained and the fabrics already attached. They even explain to me how to use my sawing machine, and how I should move on the catwalk during the show!

Sometimes it is on the contrary a big mess, just an idea, a movement…

Tell you a secret: it doesn’t matter.

Let me explain: whether the drawing is completely obsessive-compulsive, dilettante or messy, IT IS ALL PART OF THE DRAWING.

I’m not here to judge, I’m here to understand. I am the lawyer of the piece. It doesn’t matter if it’s guilty or not. I’m on its side.

And all clues are relevant.

In fact, when you receive the score, there are two different things to discover/analyze: the story — the piece itself if you prefer (and I’ll talk about this in greater detail in another article) — and its author, whom you can discern from the way he transmits, through the score, his piece to you. When you read a fiction, you feel the personality of the writer, don’t you? Through his style, his vocabulary, the length of his sentences, his chapters, etc. There’s no reason why it should be any different, simply because the language chosen is music.

It’s amazing how much you can learn about the person-composer when you take the time to really read the score! We sometimes tend to forget that there is a person behind all this, with his qualities, his faults, his doubts, his strengths, his weaknesses. I think it’s probably because, as a child, when you were given a Bach movement to learn for the next lesson, not for a second did you think (well, at least I didn’t) of the person “Johann Sebastian” behind those two pages of sixteenth notes. I was analyzing the structure, working on my intonation, trying to get a nice sound, checking my speed by working with a metronome… People talked to me about “style”. “Good taste”. In some cases they would put it in its “historical context”. But I never wondered what kind of person he was, Johann Sebastian. I took his written pages as an established object, without any connection with the human behind it. And yet. It’s essential, isn’t it, to try to understand the person who wrote the words you are about to say on stage in his name? In any event, it changes everything, I think, when you do it.

So, when you first look at this new piece, before you even get your hands on it, you’re going to get a whole bunch of information about its author. Is it a manuscript or is it edited? If it’s an edition, is it engraved by a professional or by the composer himself? How is the layout done? What does the instruction notice (if there is one) look like? How are the metronome values indicated?

With these elements one can quickly realize if one is dealing with an Exact-Sciences or a Humanities person, his experience in composition and with musicians, what is important for him.

And this is important in your interpretation, because it is the filter through which you will have to work and interpret the piece itself — the story.

For example, if you see the indication: quarter note=102.4, you might smile. Because, to begin with, between 100 and 104, the difference is very small… So 102.4! Find me a metronome that does that! But in fact, it’s not the 102.4 that is important; it’s that, as a result, the sixteenth note of a quintuplet is equal to the previous dotted eighth note, and it is very important in the eyes of the composer — important enough for him to note: “102.4”. The rhythm is therefore central to the piece he has sent you. And it shows that you are dealing with someone precise, meticulous. So when you’re going to read/analyze/work on his piece, you have to keep that in mind and put the rhythmic construction of the piece first.

On the other hand, if you have in front of you a piece without metrics, with multiple appoggiaturas/groups of fifteen small notes on each half note, you know that you are dealing with a well-read person, for which the poetry of the phrasing will come above all.

A very neat layout, well-placed page turns (I am a dinosaur, still working on paper!), tempo indications in all letters (Andante, Presto…): you are in the presence of a performer lover, who wants you to feel comfortable. Probably he will want you to put a lot of yourself/your personality in his work.

Strange graphics, rarely-used symbols, he’s an adventurer! Someone who wants you to know he is different from the others.

It would be impossible to give you an exhaustive list of all these clues, of course. Once again, I’m simplifying! There is a multitude of details to take into account, from the title of the piece to the fact that its composer only writes F flat instead of E natural. And sometimes they will be contradictory. That’s normal, we’re all human, we all have our contradictions!

But in any case, to me, it seems essential to use empathy (and understanding) when reading a new piece, and to use these clues to decipher the “story”.

That said, sometimes (often) I find that the way the piece is visually “presented” is an obstacle to my performance of it.

Let me explain.

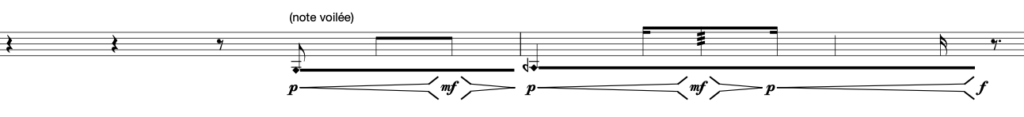

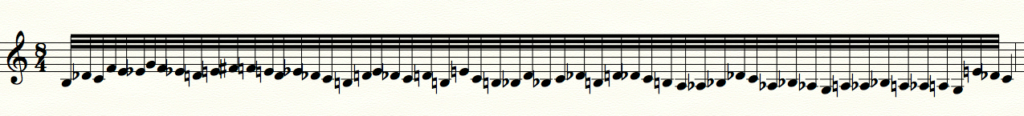

Over time, I’ve come to realize the incredible efficiency of the reflex between the eye and the hand — between reading and gesture, if you like. Before you’ve even had time to conceptualize it, you see something, you play it. In the same way, I realized that a lot of mistakes in rehearsal or in concert were caused by a doubt related to bad graphics of the score. It can be micro details, like a clumsy enharmonic:

or a poor visual distribution of the rhythm across a measure,

In these cases, quite simply, our eye “hesitates” for a few milliseconds to reorganize the information, and sometimes this leads to a mistake.

A rhythmic representation like this:

Or a lack of breath in the notation…

Sometimes it’s too much information:

In spite of the fact that these “graphics” bother me, I cannot deny that they are part of the “personality” of the score — even when they are simply due to editorial clumsiness — and that by the same token, they are useful to me in the construction of my interpretation. But as I am convinced that a fluid and comfortable reading of the text is a key element in the success of a concert, I find myself faced with this dilemma: what should be favored? The aesthetic/psychological universe of the composer, or my own reading comfort, which is the guarantee for a successful concert (and thus a satisfied composer)?

My answer was: neither. Well, both.

I came to the conclusion that the ideal is to have two scores: one with the composer’s thoughts without any compromise, and one “tailor-made” for the performance of the piece. But of course, what is comfortable for me is not necessarily comfortable for another violinist, and you can’t ask a composer to redo the score for each new performer!

So I learned how to use a music notation software, so that if I wanted to, I could make my own ideal score for the performance of the piece in concert.

Though I rarely come to this end, because it is still time-consuming — very often a bit of Liquid Paper is enough to correct an awkward enharmonic, penciling in a beat or two to rectify a bad rhythmical distribution in one measure — I will show you two examples of pieces I premiered in 2020, where I found it necessary to do so: “Black Gondola” by Erqing Wang and “Shush, overload” by Diana Soh.

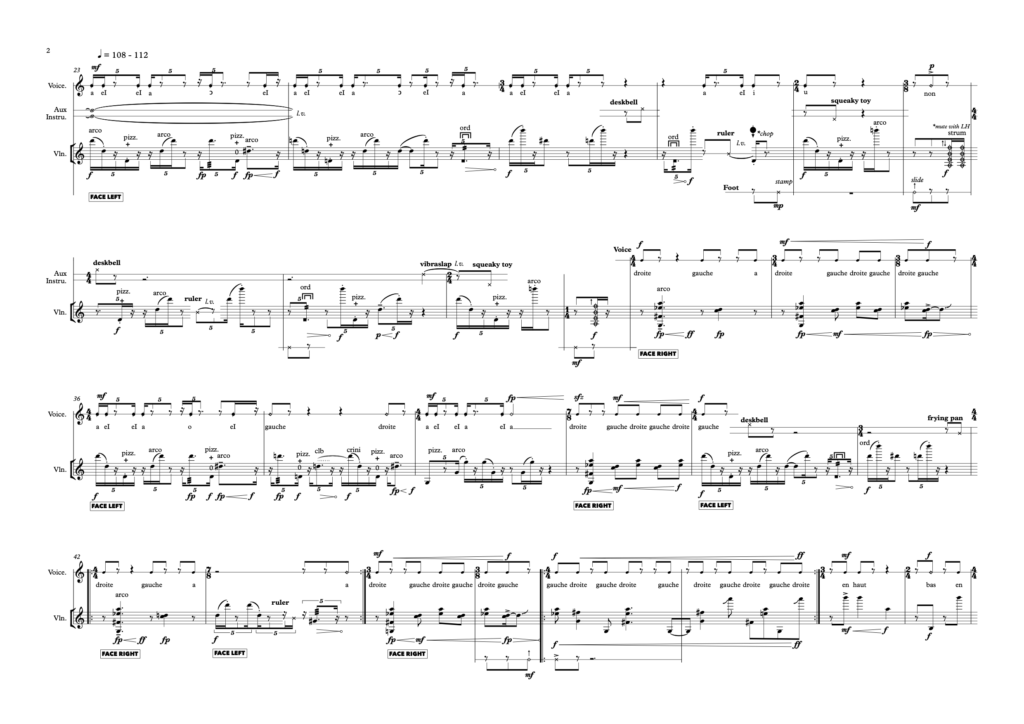

Let’s start with Diana’s brilliant piece, which I was supposed to premiere at the Biennale des Musiques Exploratoires last spring, before our dear virus decided otherwise… (I invite you to discover, if you haven’t already done so, the wonderful universe of this composer here and to go listen to the quartet which was the source of inspiration of that piece here).

The piece is written on several staves for a very simple and natural reason. Although it is a solo, I play several “instruments”: violin of course, but also whistles, vocalizations, kicks on the floor and several small “percussions”: a vibraslap, a frying pan, a desk-bell, a squeaky toy, and a ruler.

I was faced with several challenges:

- First of all, I am a violinist (!), and my vertical reading is not very developed. I mean, I can read chamber and orchestral scores like everyone else, but I don’t go very fast.

- Second, I’m a violinist (!!!), and my percussion playing is… pretty basic (but much better today, thanks to Diana).

- The vocalizations are written, as they should be, in phonetics, and since I am not a singer, this “alphabet” is not very familiar to me. (Well, it doesn’t trigger any reflexes in me, I’m forced to think, and bear in mind, this passage is all the same at 108-112 the quarter note).

- All the percussion instruments are written (as they should be, too) with notes in the shape of a cross, so I am obliged to “read” the instrument (and thus I lose time; did I mention that this passage is 108-112 the quarter note?).

- To add a little more challenge to a work that is not lacking any, the piece is slightly staged, and in this passage I have to turn around (right or left) every few bars. This results in two stands in front of each other — one on the right and one on the left — and thus the additional difficulty of having to continue on the correct bar, in the middle of all the others… In the context of a concert, this can quickly become confusing.

All this while playing the violin, of course.

So, despite the fact that the score is technically perfect, I decided to completely rewrite it, in order to minimize my reading problems — and to be able to direct all my energy and focus on performance issues!

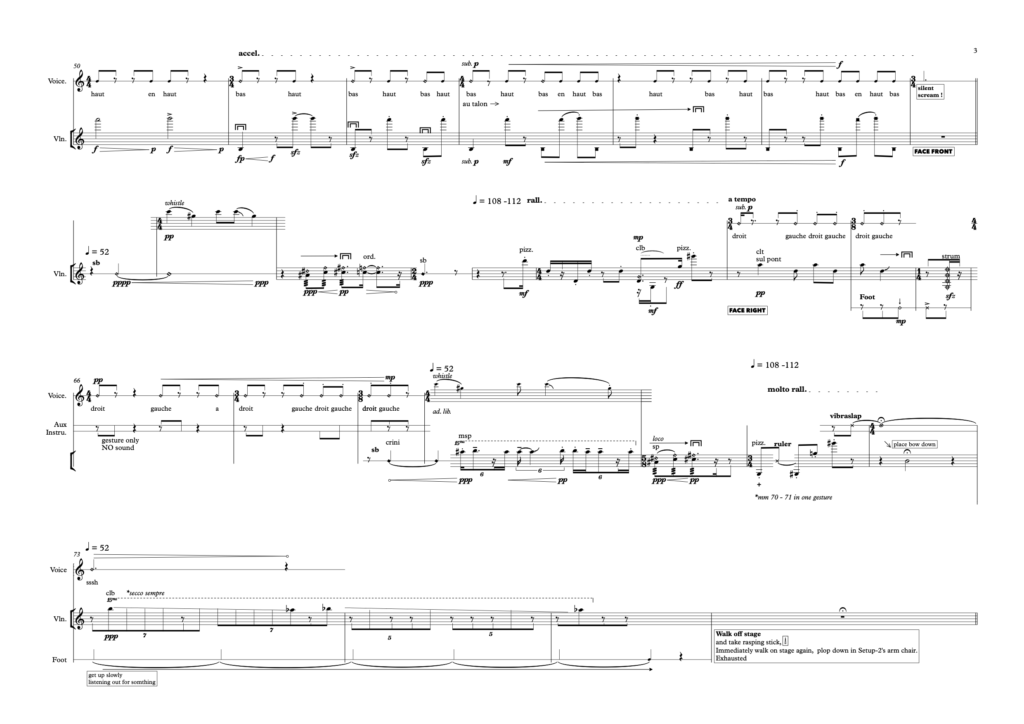

- I “tightened” everything on a single staff, for me it becomes clearer if I have a direct vision of the overall rhythm between all the instruments.

- I have “translated” the phonetics into syllables so that I will have no doubts about the proper prononciation, and these syllables have become my note heads when they are not associated with another sound/note, or added just above — like a double string — when they are. For the words “Haut” and “Bas”, I chose to put only the first letter.

- I chose different symbols for each percussion/foot movement, trying as much as possible to make them look like the instrument they represent (well, more or less.)

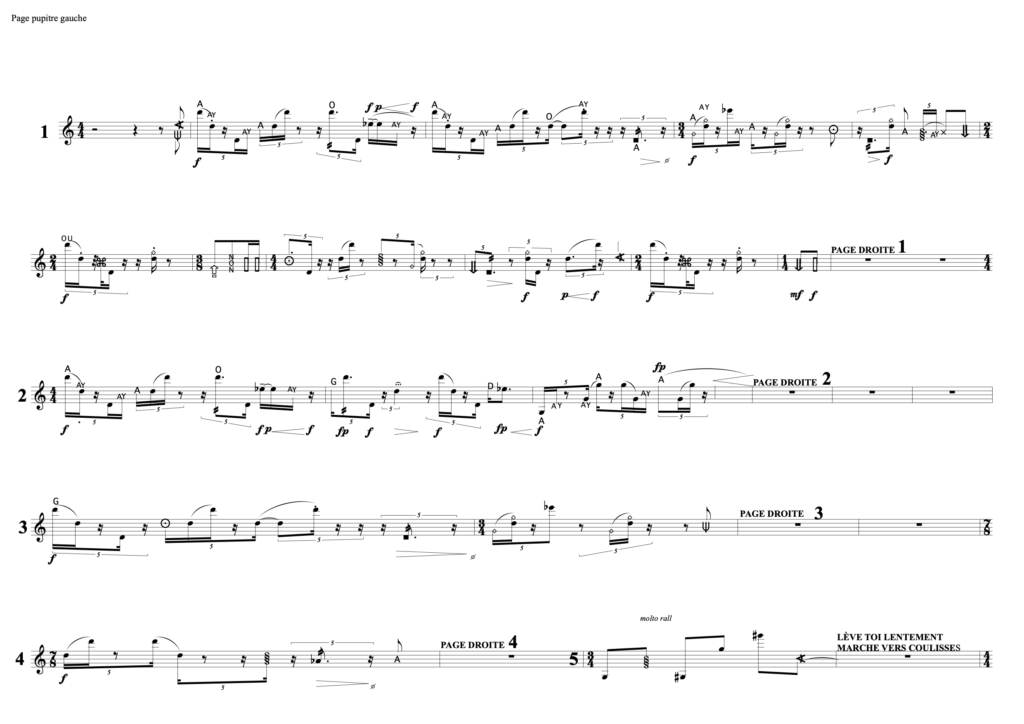

- And I made two separate scores, one for the left music stand and one for the right one, with the bar I have to play when I turn over always at the beginning of the system, indicating the order as clearly as possible, with numbers.

- I did not write the passages played by heart, because I work them from memory from the beginning of my learning, by choice.

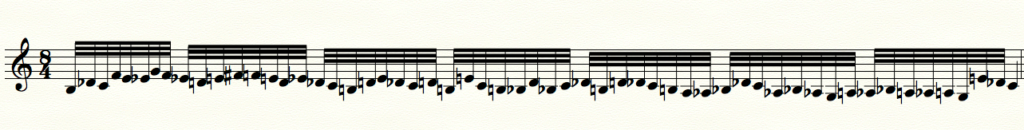

And this is what it looks like:

The left stand page:

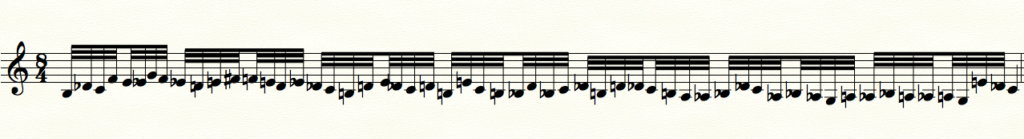

And the right stand page:

With this score, which is very comfortable for me, I can concentrate on the most important thing: the music.

In the case of the piece by Erqing Wang (a very promising young Chinese composer! If you want to know more about him, it’s here), it was a bit different. I was invited to play this piece in a recital at the New England Conservatory in Boston, where I mixed pieces from the “repertoire” with three pieces by students of the Conservatory.

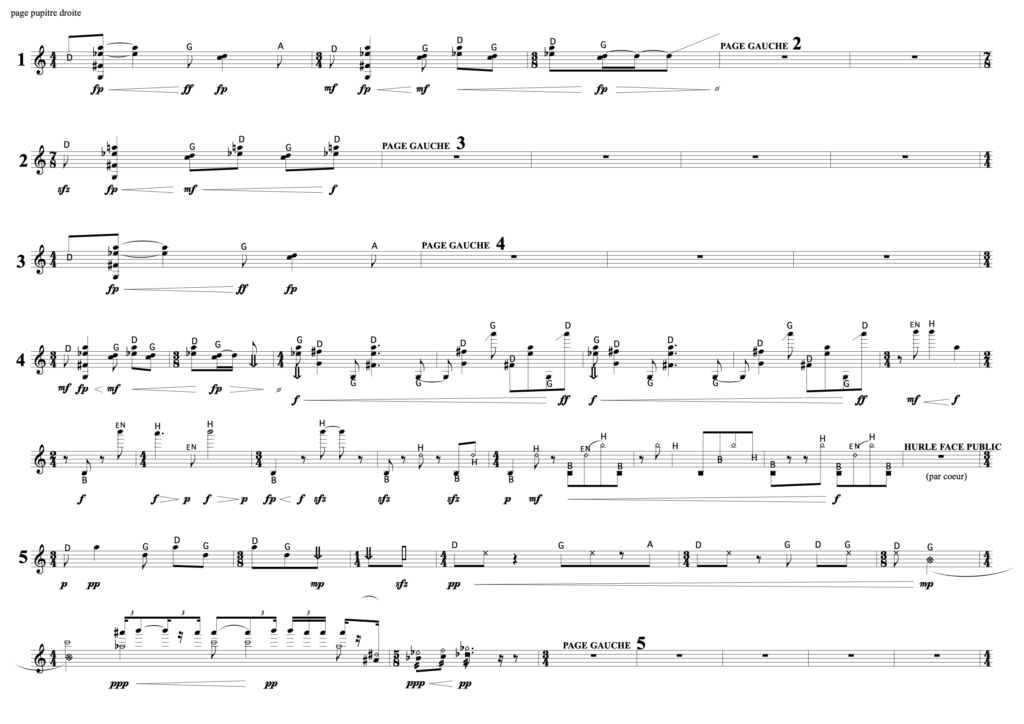

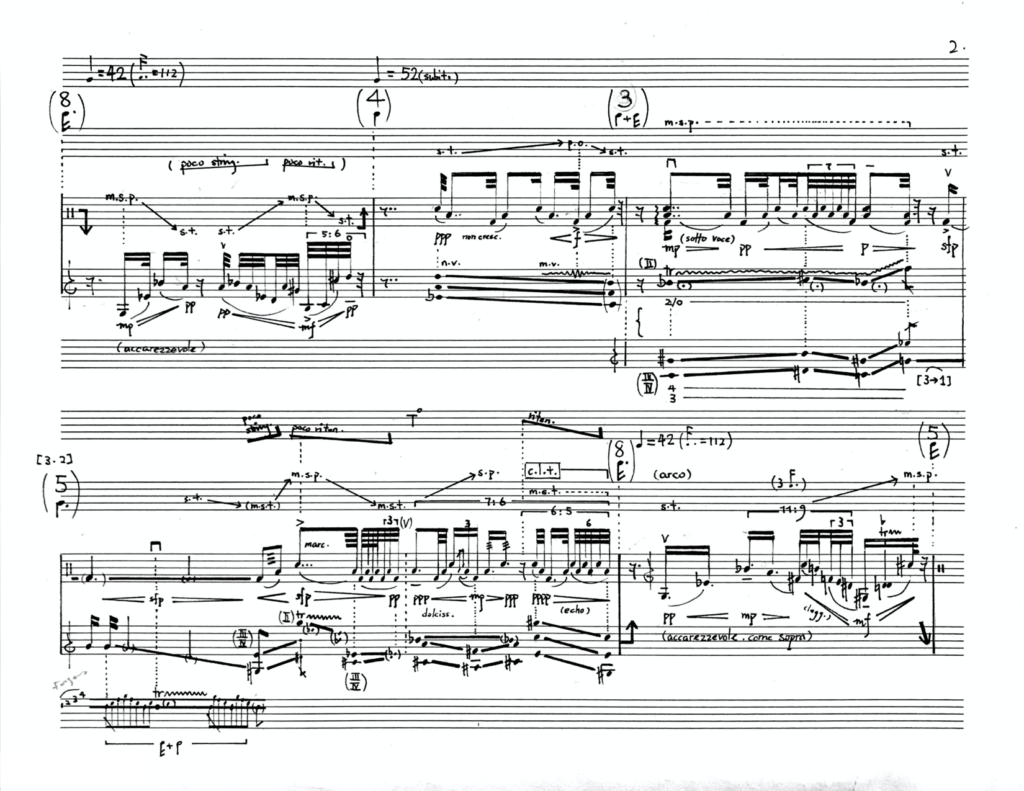

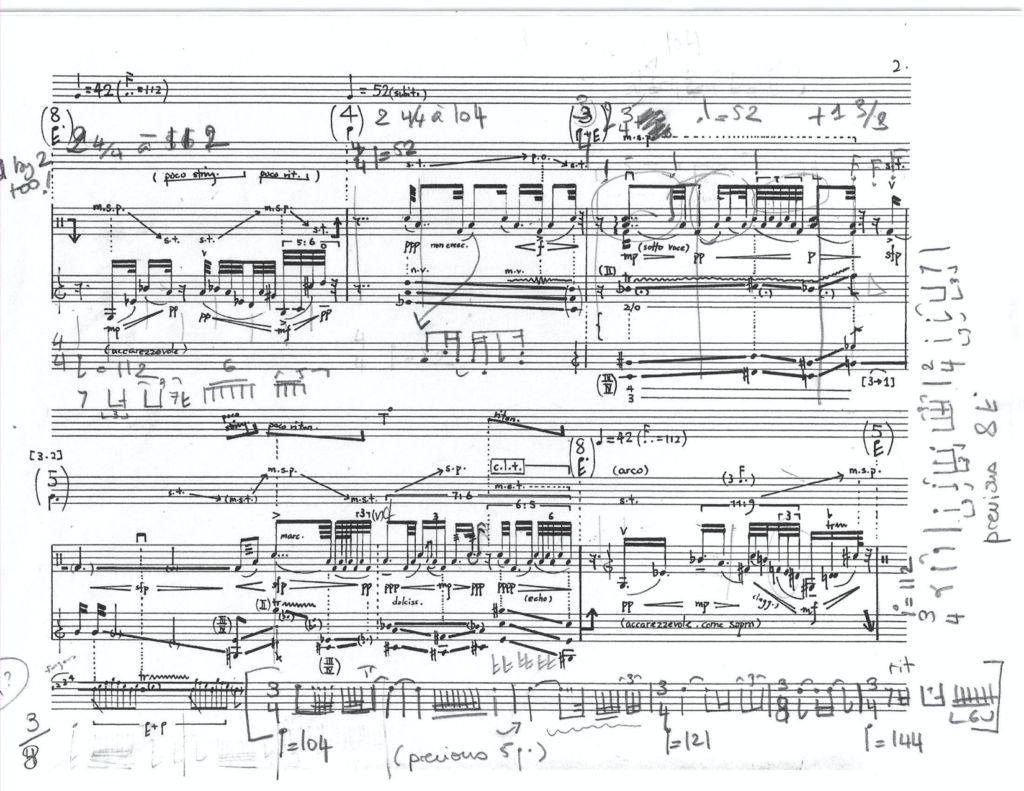

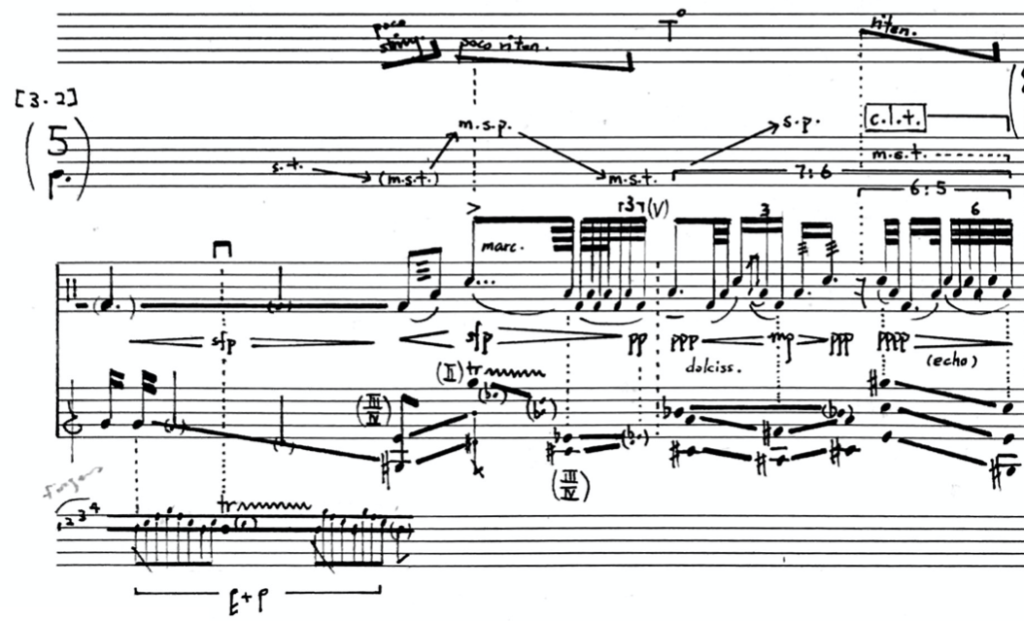

So I received, quite late (like always!), “Black Gondola”, or as I affectionately call it, “Bad trip to Venice”. Here is the second page:

My first reaction to the style of writing (an upper staff for the right hand, a lower staff for the left hand) was: I wonder what the Sibelius Concerto or Bach’s Chaconne would look like if they had decided to write using this system! Because you could write any pieces just like that… I even toyed with the idea of editing the first bars, to see if students would recognize these hits from the violin repertoire! (But hey, there are only 24 hours in a day, and it seemed a bit extreme just to make a joke). To add to the intellectual exercise, instead of writing the open strings for the right hand G/D/A/E, he decided to use F/A/C/E. Needless to say, this writing doesn’t trigger any playing reflex in me!

My second reaction was thinking: he must be a keyboardist.

Then, I must admit, I was a little discouraged. And I can assure you that I am not easily discouraged!

So I sent him an email, and to his teacher as well, asking him if he couldn’t rewrite the piece for me in a more “user-friendly” way.

A few days later, I came back to it. In addition to the left/right hand situation, the rhythmical difficulty was also overwhelming. At the same time, the piece “radiated” seriousness and precision. The more I read the piece, the more I realized that I had to “translate” it to make it more readable, more comfortable. And that I was the only one who could do it, because I was the only one who knew what I would be comfortable with!

So I began the work of translating it into the “violin language”.

Before anything else, decoding the rhythm.

When you indicate a triplet in a quintuplet in a septuplet, it doesn’t have a rhythmical feel anymore, you know what I mean? If you see a septuplet on three beats, it’s certainly more complex to set up than four sixteenth notes on one beat, but still, when I see it, I have a feeling of its velocity. When you add a quintuplet inside, then a triplet inside it, I no longer have that feeling.

I can understand the use of this kind of rhythm in an ensemble piece — and in this case I wouldn’t touch it— but in a solo piece, which in essence will be subject to a cadential effect, I wondered what Erqing was trying to tell me. Did he want to “play hard to get”, that his piece couldn’t just be sight-read? Did he want to put his performer (in this case me) in a state of panic necessary to the mood of the piece?

Be that as it may, I decided to translate his complex rhythms into changes of tempo, so that I could feel the velocity more easily.

For instance, in the first bar of the first system of the example, I decided to change the unit of time —the dotted sixteenth at 112bpm — by an eighth note. Then to make it a 4/4 at 56bpm the quarter note (or at 112 the eighth note) and to translate the rhythm obtained into triplets as indicated on the manuscript. Later, I decided to make two 4/4s at 112 the quarter note, so that there would be more homogeneity between the tempi of the passage.

And I treated all the measures of the piece, taking extra care NOT TO MODIFY anything rhythmically. I just changed the “spelling”.

In doing this work, It occurred to me that Erqing might have wanted me to feel unstable through these complex rhythmics — that instability was central to his piece. A bit like being on a gondola! At least that’s how I understood it. So I promised myself that, even if I translated the rhythm into something more comfortable, I would keep this feeling as the central idea of the piece.

After this decoding process, the editing of the score began.

A large part of the piece is built on left hand glissandi, with a strict rhythm on the right hand.

Little by little I “accepted” the idea that if Erqing had decided to write his piece this way, it was because he had no better one. It would be hard to do it any other way. By editing it “my” way, I was already making decisions about my performance, and that made my material unusable for other violinists.

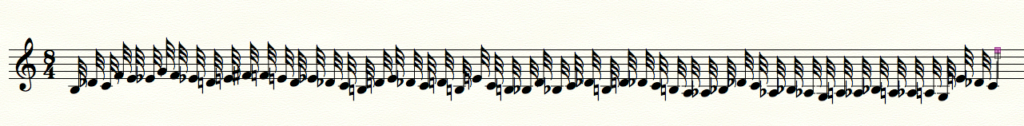

I made the decision to translate the glissandi as well, but in order to respect the composer’s wishes as much as possible, I decided to put the glissandi start and end notes in normal size, and everything in between in much smaller one (because they are not fixed) — I considered putting them in brackets for a while, but this made the score too “messy”. I also set up a special notation for the groupetto/glissando at the beginning of the second system, because writing down the pitches, even approximately, would have generated a “fingering” reflex: I had to find a graphical way to keep my left hand in a glissando reflex. In the end, a glissando with “note heads/fingerings” proved to be quite effective.

I ended up getting this:

I did not put any written indication of ponticello, tasto or legno: I decided a long time ago to use a color system for the “modes de jeu”, in order to limit as much as possible the need to read above and below the staff, and to keep my reading line as fluid and uninterrupted as possible (but I’ll have the opportunity to tell you more about this later!).

In conclusion, I would say that after spending these many hours “in the company” of Erqing (through his score) my feeling is that there is a lot of meaning behind such a complex notation. Perhaps he wanted his performer to make an effort, that nothing was obvious. It also crossed my mind that maybe he just wished to be taken seriously.

In any event, it is certain that the “writing” of his piece, despite the fact that it was “unreadable” for me and that I played on custom-made material, had a great influence on the way I worked and interpreted his piece. And I think it’s a fantastic piece!

Do not hesitate to contact me for questions or remarks, propose a subject for a new article, I will try to answer it as best I can!

And subscribe here if you wish to be informed about new articles.