On this page you will find:

- The performance of micro-intervals on the violin and their notation

- The display of accidentals in a contemporary score

- Practicing quarter tones (for instrumentalists)

THE PERFORMANCE OF MICRO-INTERVALS ON THE VIOLIN AND THEIR NOTATION

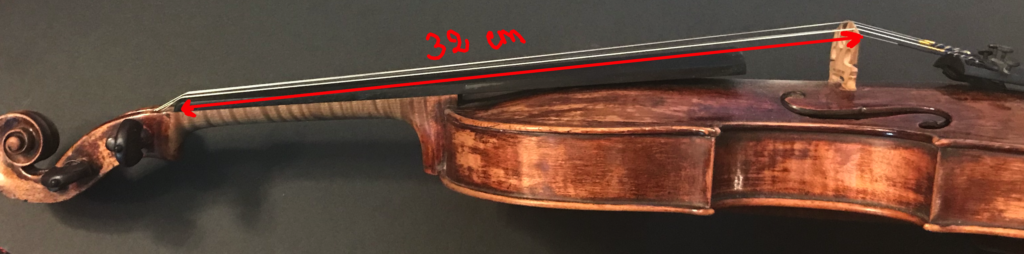

Before getting to the heart of the matter, i.e. the micro-intervals, let me introduce you to (or remind you of!) a few basic dimensions of the violin “geography”; after all, you probably don’t have one at hand, and even if you did, it probably never occurred to you to measure those (I myself had never done that before I started writing this article!!).

On my violin — a charming (isn’t it?) Sebastian Klotz dating 1766 — one string, from nut to bridge, measures about 32cm (if necessary, go have a look at this article for a reminder of the anatomy of the violin)

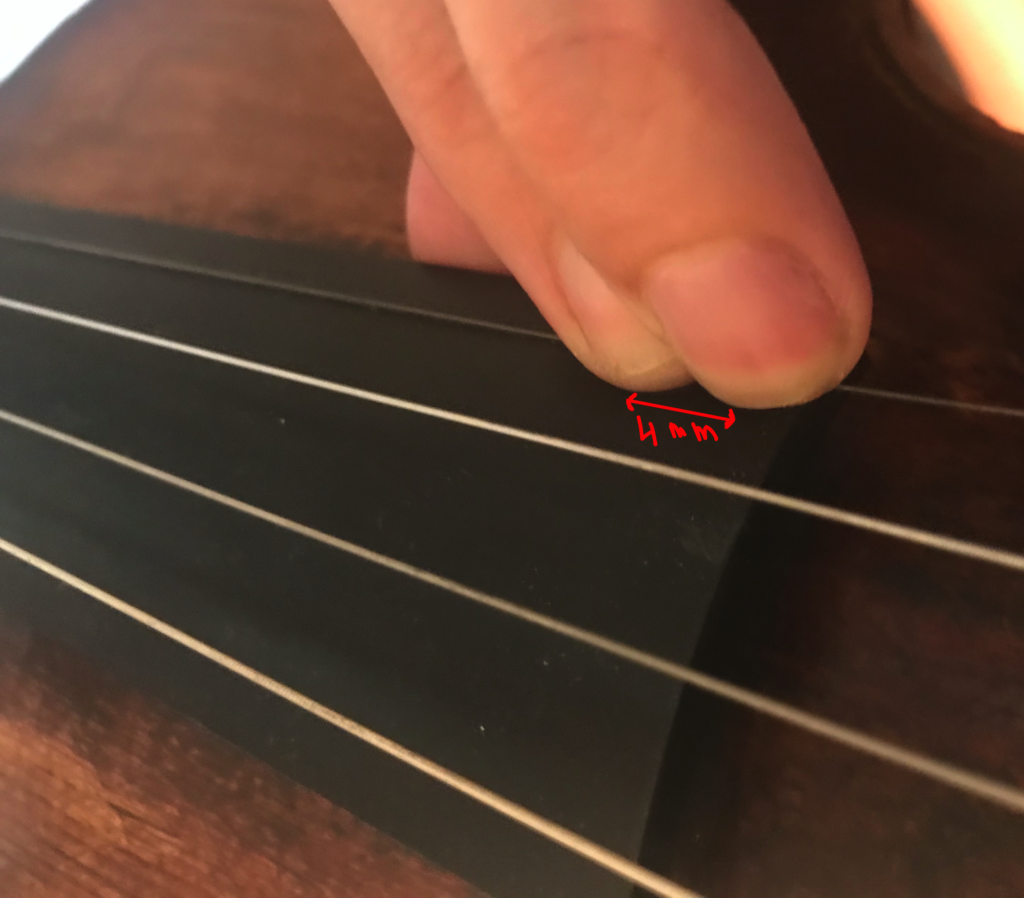

The tip of my index finger is 8mm deep by 11mm wide.

Yes, I know it’s surprising, but don’t forget that after having spent thousands of hours (tens of thousands?) practicing — meaning pressing your fingertips on a small ebony board — they have fortunately a slight tendency to get flattened and to be covered with calluses, because otherwise it hurts a little bit…

The “first tone” placed with the first and second fingers — index and middle fingers — measures 32mm.

As it turns out, the higher you go up the string (for the newcomers: the closer your hand gets to the bridge), the shorter this distance gets (to learn more about the range of the strings, have a look at this article). So no two tones on the same string measure the same distance.

At the very end of the fingerboard, a tone equals 4mm.

You will tell me: “But your finger is 8mm thick!”

Yes, it is indeed a problem.

But hey, solutions have been found for centuries: substituting fingers, modifying the pressure of the finger on the string, playing joint notes with the same finger, etc. But you have to understand that, even with these thousands of hours of work mentioned above, you will NEVER be as precise and swift at the end of the fingerboard as elsewhere.

And why am I bothering you with all these measurements in millimeters?

Well, I would like you to get a more “concrete” idea of what micro-intervals mean in terms of difficulty on the violin. So we have said that the “first tone” (A![]() -B

-B![]() on the G string, E

on the G string, E![]() -F on the D string, B

-F on the D string, B![]() -C on A and F-G on E) measures about 32mm.

-C on A and F-G on E) measures about 32mm.

It means that:

- a semi-tone is 16mm

- a third of a tone is 10,66mm

- a quarter tone is 8mm

- an eight of a tone is 4mm

And at the end of the fingerboard,

- a tone: 4mm

- a semi-tone: 2mm

- a third of a tone: 1,33mm

- a quarter tone: 1mm

Uh, I’ll stop there, ok?

This is why it is advisable to avoid quarter tones in the upper range of the violin. Here a simple change of finger pressure on the string makes you raise or lower the note by almost a tone… Not to mention the fact that, even with a very good ear, you start having trouble hearing them.

As you “go further down” to the low pitch string instruments, viola, cello, double bass, the average length of the string increases, hence the distance between the fingers to play a tone. However, the fingers are always more or less the same size…

Having longer strings presents other difficulties, but for the micro-intervals I must say I find it to be quite practical!

Of course, the older and more used the technique is, the more the notation tends to stabilize. This is normal. Quarter tones, on the scale of the evolution of the violin technique, are prehistoric!

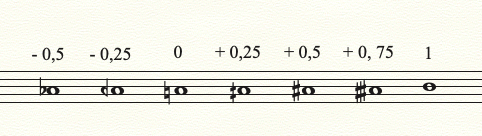

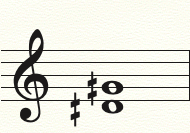

On most of the scores that find their way to my music stand, the quarter tones are notated like this:

Over the past twenty years, the notation seems to have stabilized on this. Yes, I know, there is also a heart-shaped double flat for the lower triple quarter-tone, but frankly, considering the possibility of enharmonic equivalents, it’s been a while since I saw it on a score!

If this is the system you use, don’t even bother mentioning it in your instructions: any musician vaguely interested in contemporary music knows what it is all about. If this is not the case, consider entrusting your creation to someone else…!

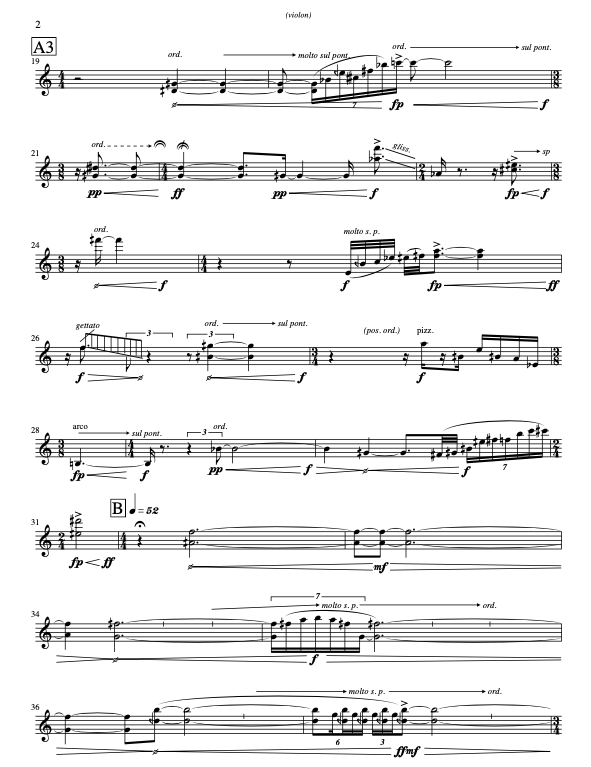

The third, sixth and eighth tones remain much rarer. The notation of accidentals with up or down arrows seems to be becoming the norm for indicating eighth of tones, as here in Philippe Leroux’s “Postlude à l’épais”:

Warning for instrumentalists: in older pieces, it is possible to find this notation on “normal” accidentals to indicate quarter tones!

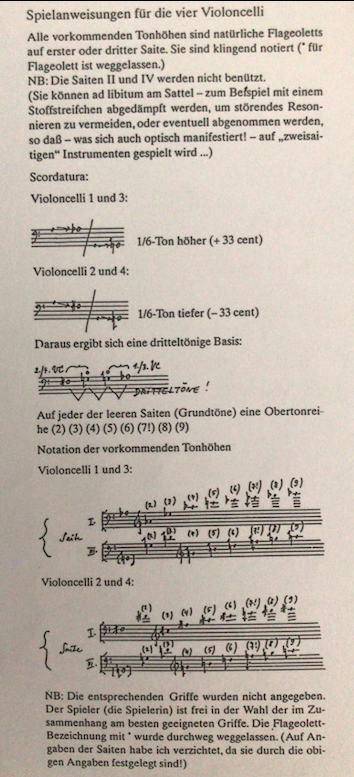

Personally, I have never played pieces requiring third of tones or sixth of tones, but I invite you to listen to this very beautiful piece by Klaus Huber, “…ruhe sanft… im memoriam John Cage” (listen here) for four cellos, recorded by my dear friend Alexis Descharmes, which uses the division of the tone into three equal parts.

The color obtained is indeed very different from the division into four quarter tones, and the technique used by Huber is very clever and efficient. The 4 cellos are tuned, with scordatura, using a tuner: the D and C strings are tuned normally; cellos 1 and 3 lower their A string by one semitone, and raise their G string by one sixth of a tone; cellos 2 and 4 lower their A string by a minor third (an F![]() ), and their G string is lowered by one sixth of a tone.

), and their G string is lowered by one sixth of a tone.

This is the part of the instructions explaining the process (in German):

By using only open strings and natural harmonics on the “scordaturated” strings, Huber ensures a division of the tone into three between the different instrumentalists, thus creating a sound universe of thirds/sixths of tone without asking his performers for a perfect ear or an exceptional digital technique.

I have to admit that micro-intervals other than quarter tones do not seem very practical to me — difficult to hear, delicate to feel digitally. In the case of an eighth tone, I refer you to what I said above: we are still at best (in the first position) on a distance of 4mm, while my finger is already 8mm deep.

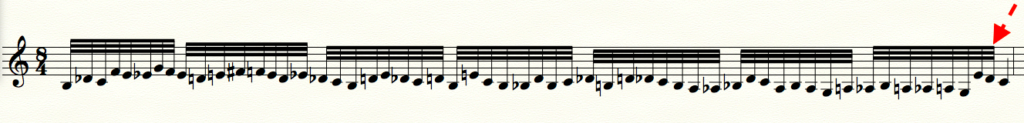

While I always do my best to perform them as precisely as possible, I must confess that I am never 100% sure of my accuracy, especially when I find them scattered in a fast passage. They seem more achievable to me — but still not comfortable — when they are isolated by a good silence of preparation, or if the whole passage must be raised or lowered by an eighth of a tone: I practice the “tempered” sequence, then I incline my hand ever so slightly forward to “add” this eighth of a tone to the whole sequence, for example in Christophe Bertrand’s “Satka”:

However I ask myself the following question:

Isn’t what I feel, when faced with these thirds and eighths of tones, similar to what performers at the beginning of the twentieth century might have thought when faced with these “new” quarter tones? Didn’t they think: “but it’s impossible, it’s too small, I can’t hear them etc.”? Probably. And yet today they are common, no one is surprised anymore. The technique has evolved, because composers have continued to use them regularly, instrumentalists have found solutions to make them achievable and, by practicing them regularly, they have ended up hearing them almost perfectly.

In short, they have entered the common technique.

Would I feel the same way if I were to regularly play pieces using thirds, sixths and eighths of a tone, or are we reaching the limits of the human ear and our digital skills? Far be it from me to venture an answer to this question.

Nevertheless, here are a few personal thoughts:

Over the last ten years, I have repeatedly encountered technical difficulties that I have judged “impossible”. Sometimes, I still do. But I have to admit that, with (sometimes hard) work, some of them have shifted from the “impossible” to the “feasible”. That’s one of the pleasures of working in this field: you’re constantly pushing the limits of the possible.

So, as a matter of principle, I never say “never”.

However, be aware of this difficulty, and if you decide to compose using thirds/sixths/eighths of a tone, do so with the knowledge that the result might not be 100% accurate.

Also take the time to explain your notation of these micro-intervals in your instructions.

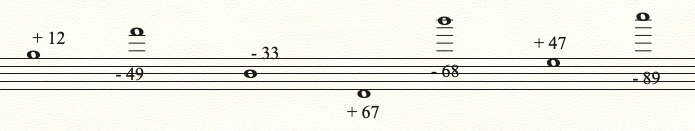

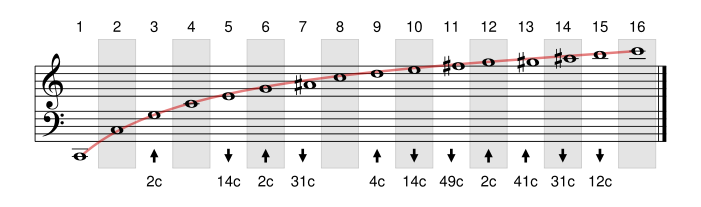

I remember an amusing anecdote when, during a composition workshop, a student handed me something like this to play:

My first reaction was: “it’s flattering — this young composer thinks I can hear the cents perfectly”. Then, when I thought about it, it was a bit insulting… How can I put it… I felt a bit dehumanized, treated a bit like a computer.

This is a typical case of theory versus practice.

I suppose that this notation made sense in the composer’s mind (though don’t look for it in the example above, I chose random numbers!). On the other hand, for me, despite the fact that I understand the thing in theory, reading this excerpt does not trigger any playing “reflex”.

In order to play it successfully, I would have had to translate it using accidentals…

Having said that, the effectiveness of the notation is not everything in a score: this very precise and mathematical notation allowed me to understand a little better the personality of this young composer, which is extremely important in the context of an interpretation! But I will have the opportunity to tell you more about it in this other article.

THE DISPLAY OF ACCIDENTALS IN A CONTEMPORARY SCORE

Nowadays, many composers use music notation software themselves. On these programs, the default function of displaying accidental alterations is classical, i.e. once per bar and per octave.

While this technique is quite effective in the tonal context of the “classical” repertoire (for want of a better term), it is not at all adapted to the contemporary repertoire. And yet, 90% of the scores I receive use it…

Let me explain:

Most of the time, contemporary pieces are performed in concert with the score (given the technical difficulty, memorization is extremely difficult, if not impossible).

A fluid reading of the text is therefore a key element for success.

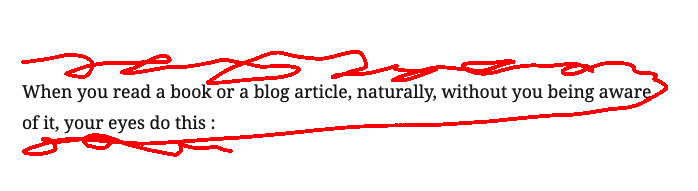

When you read a book or a blog article, naturally, without you being aware of it, your eyes do this:

They move forward, backward, they stop, start again…

A professional musician has trained his eyes to minimize these back and forth, to get as close as possible to a straight line. This, among other things, allows him to process and execute in the right order a whole myriad of information in a very short time.

Here is an example, very freely inspired by a sequence from Martin Matalon’s magnificent piece “Traces VIII” for violin and electronics:

Tell me, the D under the arrow, is it natural? flat? sharp?

Take the time to analyze what your eyes have done: they went backwards, looking for the last D with an accidental.

In the context of a passage around 70 the quarter note — which is already a respectable speed in thirty-second notes — if there’s one thing you don’t want, it’s for your eyes to wander off! In any case, by the time you’re going backwards to look for the missing information, your finger has already landed, quite naturally, on a D (since there was no accidental on it: your fingers are very logical).

That’s why 99% of musicians will pencil in this flat.

When it’s an isolated problem, it’s not a big deal. But when you find yourself penciling in accidentals on almost every note of a passage, it becomes messy, sometimes even unreadable. And the messier a score is, the more likely it is for the performer to make mistakes.

This cannot possibly please neither the performer — who in all likelihood is striving to give as perfect a performance of the piece as possible — nor the composer, who generally does not look favorably upon inaccuracies in the performance of the piece he took months to compose. And it’s a pity, a simple manipulation on your score editor can force the display of all accidentals!

Whichever system you choose, above all: stick with it from beginning to end. There is nothing more disturbing than — when at the 17th bar of a piece with all the markers of a classic display of accidentals — all of a sudden, at the third and fourth beat, 2 G![]() follow each other for no reason at all. Is this an error due to an unfortunate copy-paste? Or were the first 17 bars in fact in “one accidental per note” mode and a few naturals were missing? You don’t want your performer to doubt each and every note!

follow each other for no reason at all. Is this an error due to an unfortunate copy-paste? Or were the first 17 bars in fact in “one accidental per note” mode and a few naturals were missing? You don’t want your performer to doubt each and every note!

PRACTICING QUARTER TONES

I will now address more particularly the instrumentalists among you, because during my master classes I am regularly asked this question: “How to play quarter tones perfectly in tune?”

First of all, no, no, no and no, playing quarter tones is not playing out of tune.

(What a horrible thing to say!)

This fourth,

in the absence of any other reference-note, sounds perfectly in tune.

Secondly — I am not teaching you anything — the quarter tone is not a modern invention, it is a natural component (as well as the sixth of tone) of the resonance of a note.

Your note would not be quite itself without the micro-intervals!

I must admit that — despite the somewhat “scientific” approach of this article so far — for me, quarter tones have always been a very colorful, very emotional tool.

I feel a slightly greenish shade, a feeling of “shoes sticking on the ground” with a lower quarter tone, and an orange shade, very luminous, a feeling of a “stretched elastic on the verge of breaking” with the upper quarter tones.

I love it when they appear in a very melodic context, as if for a moment you get a glimpse something not quite “normal” in a classic beauty context: a scar, a misplaced mole: it’s ugly, but it’s beautiful. I remember that my eighth grade French teacher introduced us to a work by the Finnish painter Juhani Linnovaara, which depicted a hyper realistic nature scene with a monster’s head in one corner. He told us that the monster “proclaimed its difference”. It made an impression on me, don’t ask me why! Well for me it’s exactly that: in a melody, the quarter tones proclaim their difference, as in this very beautiful piece (listen here) by the composer Chaya Czernowin.

Small exercise:

Take your violin, play a third B-D, on the A string, in 1st position.

Forget everything your teachers have taught you so far, and put the 2nd finger — the C — EXACTLY BETWEEN THEM.

You should have a perfect C![]() . The distance you feel between your fingers is 0.75 tone, which is half a tone + a quarter tone. It is normal that this distance seems strange to you at first. That will pass. (Well, if you keep practicing, of course).

. The distance you feel between your fingers is 0.75 tone, which is half a tone + a quarter tone. It is normal that this distance seems strange to you at first. That will pass. (Well, if you keep practicing, of course).

Play for a moment with these three notes, your brain may try to get you back into the “normal”, the tone. Resist, and enjoy this feeling: you are a rebel!

Now, stay a little on this C![]() , and add the open E: it makes you cringe? Then it’s in tune.

, and add the open E: it makes you cringe? Then it’s in tune.

For the quarter tones as for all other techniques, the rest is just work. The more you work on this repertoire, the more natural this division of the tone will be, and after a while the quarter tones will seem just as obvious as the semi tones.

To achieve this result, and to try to be as precise as possible in this “new” tuning, I think you have to work on the way the notes relate to one another (as always), choose your reference-notes and the order in which you place them. By choosing your reference-notes, you decide the “temperament” — for lack of a better word I will use this one — in which you will think your intervals. It can be a quarter-tone temperament, if you choose a quarter-tone or three-quarter-tone note as reference — in which your sharp, flat and natural notes will sound foreign — or a natural temperament, if you choose a sharp, flat or natural note as a reference — in which it is the quarter-tone and three-quarter-tone notes that will sound foreign. Everything is relative, as Albert used to say, right?

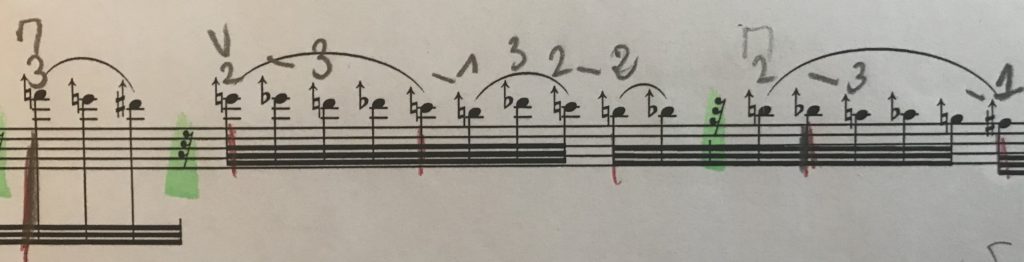

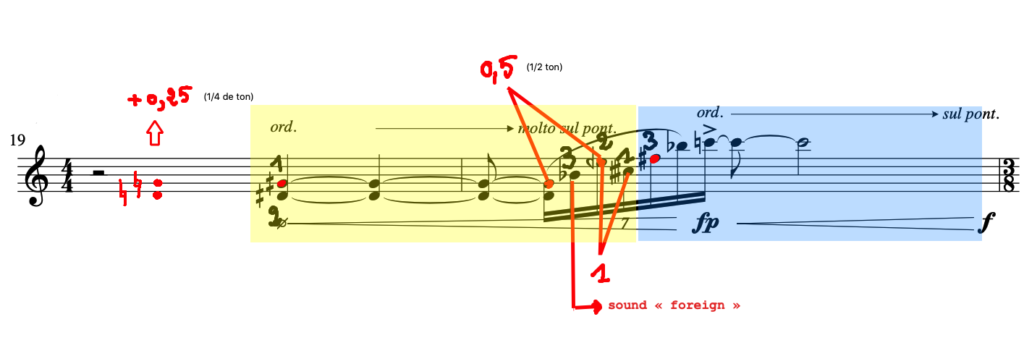

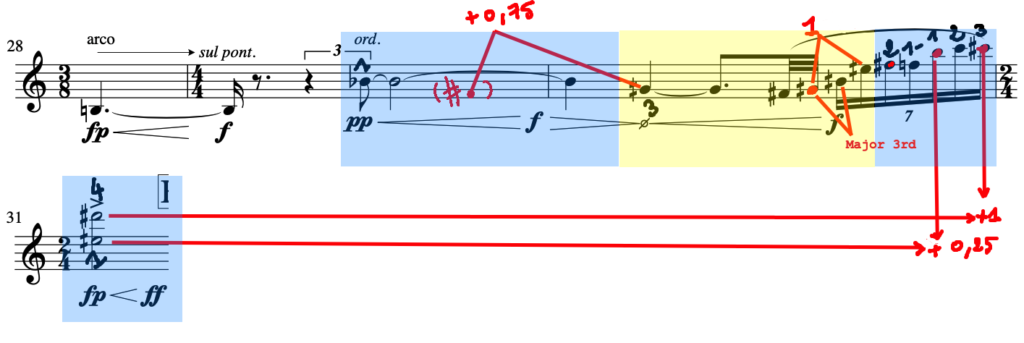

I realize that this last paragraph may seem a little obscure. To explain what I mean by this, I will take as an example the second page of “So nah, so fern” by my friend Philippe Hurel, I will indicate in red these famous “notes-references” and indicate in which temperament I am thinking at any given moment: in blue my reference is natural, in yellow it belongs to the universe of the quarter tones.

Here it is:

Take bars 19 and 20:

As I said earlier, this fourth must sound in tune. Therefore, during the silence, I place the fourth D![]() -G

-G![]() in 3rd position and move it a quarter tone up.

in 3rd position and move it a quarter tone up.

Then I notice that the E![]() is at a “normal semitone” distance from the G

is at a “normal semitone” distance from the G![]() , and the C

, and the C![]() is exactly one tone lower. So E

is exactly one tone lower. So E![]() and C

and C![]() must sound perfectly in tune (like E

must sound perfectly in tune (like E![]() -D

-D![]() ), but when you check C

), but when you check C![]() with the open D, it should make you cringe!

with the open D, it should make you cringe!

In other words, my fourth D![]() -G

-G![]() is a reference for my fourth D

is a reference for my fourth D![]() -G

-G![]() , my G

, my G![]() is a reference for my E

is a reference for my E![]() , itself a reference for my C

, itself a reference for my C![]() . Up to this note, we are in a kind of temperament raised by a quarter tone, in which the B

. Up to this note, we are in a kind of temperament raised by a quarter tone, in which the B![]() sounds foreign, at a distance of 1.25 tones from the G

sounds foreign, at a distance of 1.25 tones from the G![]() .

.

To return to the natural temperament, put the F![]() at a distance of 2.25 tones from the C

at a distance of 2.25 tones from the C![]() (actually, imagine that this C

(actually, imagine that this C![]() is a D). The placement of the F

is a D). The placement of the F![]() would be obvious. So take this evidence then add a quarter tone. From here on, you’re in the clear!

would be obvious. So take this evidence then add a quarter tone. From here on, you’re in the clear!

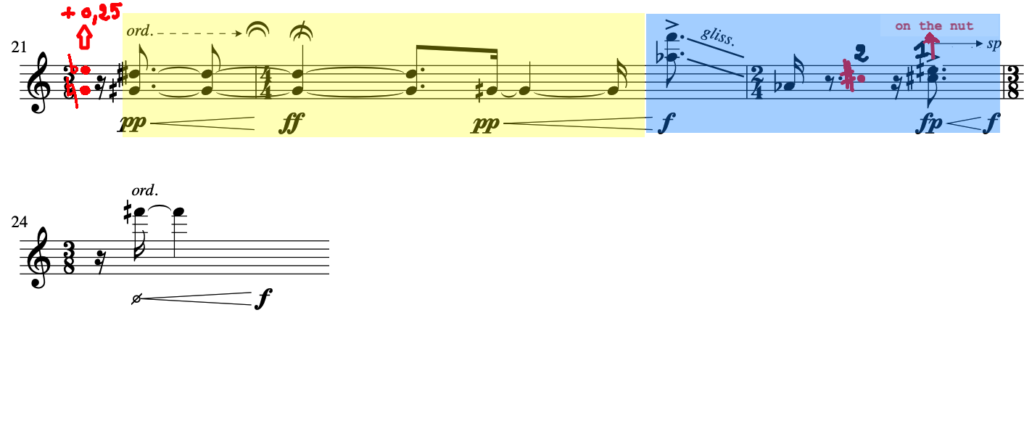

Bar 21,

I place in the silence G![]() -E

-E![]() then I move it a quarter tone upwards.

then I move it a quarter tone upwards.

At the end of bar 23, I first place the C![]() , then I place the first finger as close as possible to the nut on the E string. For me, I remain in a normal temperament and it is the E

, then I place the first finger as close as possible to the nut on the E string. For me, I remain in a normal temperament and it is the E![]() that sounds foreign so, using the nut as a reference, it is easy to place.

that sounds foreign so, using the nut as a reference, it is easy to place.

For the F![]() that follows, I just think of a “bright orange” F

that follows, I just think of a “bright orange” F![]() . Someone else might think of it more as “too optimistic”, “too high”, or even, an F

. Someone else might think of it more as “too optimistic”, “too high”, or even, an F![]() “too low” etc. Give it a try, find the thought that will work for you! (And check with the open A to verity that it makes you cringe as well as it should)

“too low” etc. Give it a try, find the thought that will work for you! (And check with the open A to verity that it makes you cringe as well as it should)

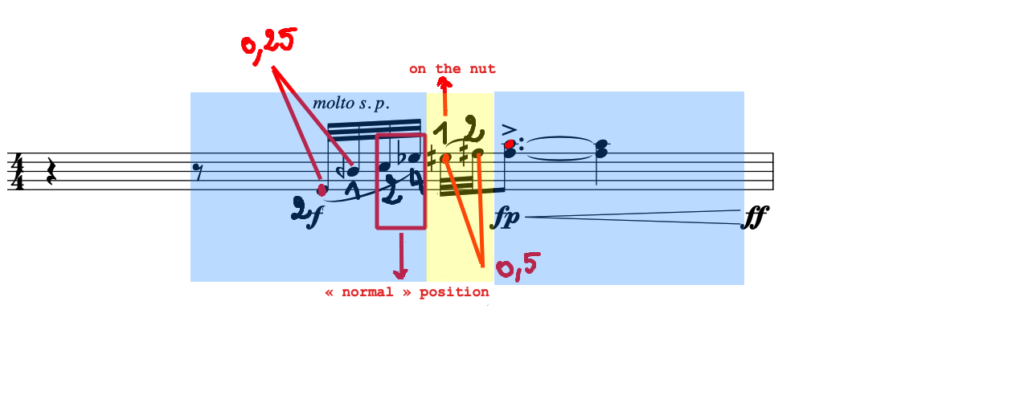

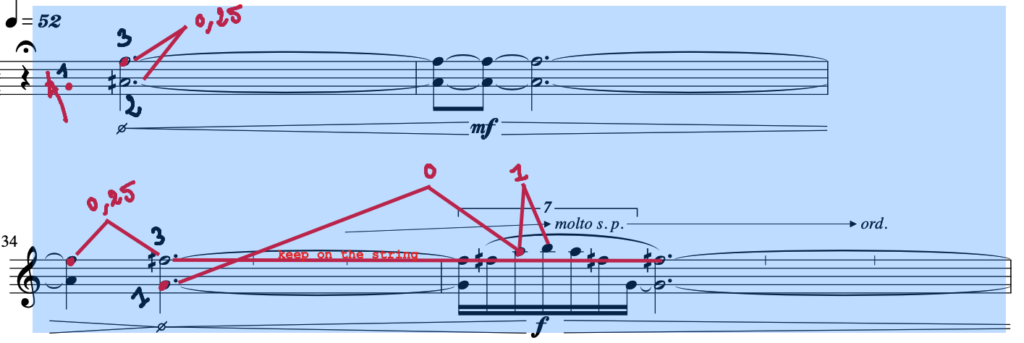

Bar 25,

I place my second finger on the E, then I place the first finger very close, the C and the E![]() in their usual places, the E

in their usual places, the E![]() straight after the nut and the F

straight after the nut and the F![]() at a “normal” semitone.

at a “normal” semitone.

Bar 26,

I place B![]() -G

-G![]() and raise them by a quarter tone, and I keep the B

and raise them by a quarter tone, and I keep the B![]() in place for the rest, since it will be my “foreigner” in the pizzicato descent.

in place for the rest, since it will be my “foreigner” in the pizzicato descent.

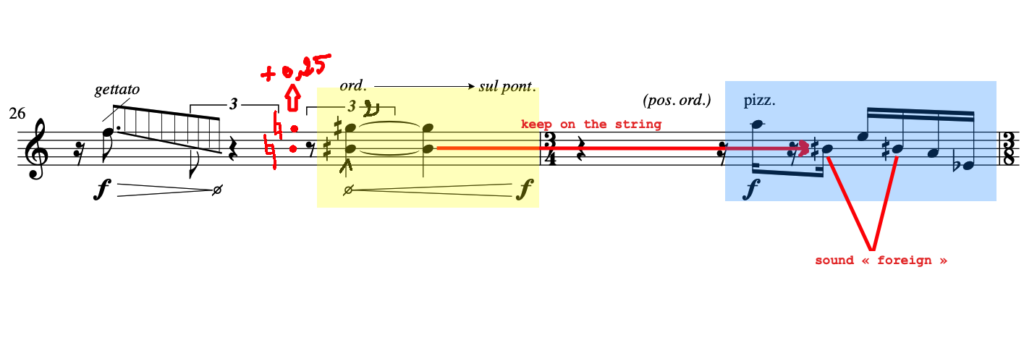

Bar 29,

I place the F![]() under the B

under the B![]() from the start, to prepare the G

from the start, to prepare the G![]() . I find the distance of 0.75 tone (our famous C

. I find the distance of 0.75 tone (our famous C![]() from earlier, remember?) easier to feel digitally than the third B

from earlier, remember?) easier to feel digitally than the third B![]() -G

-G![]() . Then I place the B

. Then I place the B![]() and E

and E![]() according to the G

according to the G![]() (normally between them in fact, although a quarter tone higher than usual), and then I’m good for the rest of the septuplet. For the seventh E

(normally between them in fact, although a quarter tone higher than usual), and then I’m good for the rest of the septuplet. For the seventh E![]() -D

-D![]() , I think the D

, I think the D![]() a tone higher of the preceding C

a tone higher of the preceding C![]() , and the E

, and the E![]() a quarter tone higher than I had played the B, but on the A string.

a quarter tone higher than I had played the B, but on the A string.

Then,

I place the seventh G![]() -F

-F![]() as early as bar 32, adding the A

as early as bar 32, adding the A![]() as close to the F as possible. In measure 34, I just raise the F by a quarter tone (since I have prepared my G), and in the “bariolage”, bar 35, I’m careful to place the A

as close to the F as possible. In measure 34, I just raise the F by a quarter tone (since I have prepared my G), and in the “bariolage”, bar 35, I’m careful to place the A![]() parallel to my G

parallel to my G![]() without moving my F

without moving my F![]() .

.

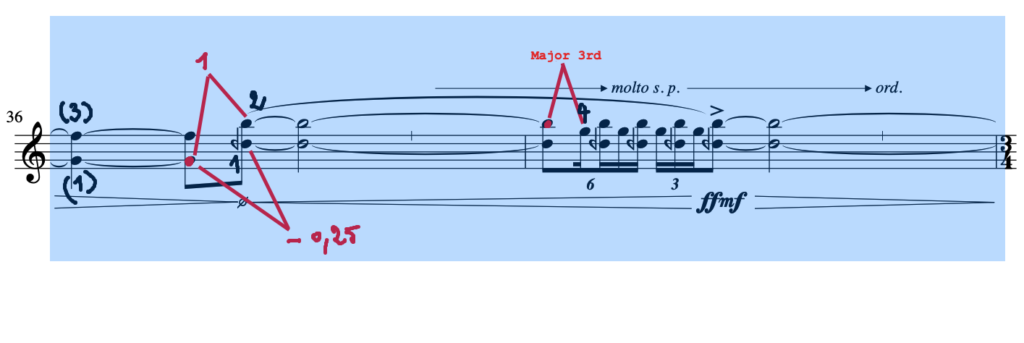

Finally, for bar 36,

I place the B![]() at a one tone distance from the G (but on the E string), then the D

at a one tone distance from the G (but on the E string), then the D![]() a quarter tone lower than the G (but on the A string). After that it’s simple, just put the G

a quarter tone lower than the G (but on the A string). After that it’s simple, just put the G![]() according to the B, not the D

according to the B, not the D![]() .

.

Do you follow me? In fact, to play all this strictly in tune, you just have to decide what you place according to what. Which notes you decide to relate. Prefer the fingerings that seem familiar to you (for example, I’m always more sure of my A![]() in 1st position right on the A string nut than in 3rd position on the D string).

in 1st position right on the A string nut than in 3rd position on the D string).

And then, with time and work, you realize that you play the quarter tones in tune (almost) without thinking about it — you have created a reflex between the notation and the gesture — as it has always been the case with sharps and flats…

Do not hesitate to contact me for questions or remarks, propose a subject for a new article, I will try to answer it as best I can!

And subscribe here if you wish to be informed about new articles.